Dunning-Kruger Nation

The Power Struggle Between Instructional Learning and Non-Instructional Educational Positions Will Decide if Higher Education Values Learning or Passing

The 2023 debate over California’s fifty-percent law, a five-decade old law that requires the Golden State’s community colleges to allocate a minimum of 50 percent of their funding to instructor salary and benefits, reveals that non-instructional staff and administrators’ vision for the future of higher education is one where instruction is a minor, if not non-existent part of education; learning is less valued than passing; and how students feel about the content is more important than its utility or veracity.

The process by which we got here began with the post-1970s phenomenon of administrative bloat, which reduced the percentage of instructors in the education process. From 1976 to 2018, full time administration positions increased 164 percent and other professional positions increased 452 percent, while full-time faculty positions increased by 92 percent. Meanwhile, student enrollment only grew by 78 percent. Indeed, some schools such as Yale University reported having as many administrators as students. On average, universities and colleges have three times as many administrators as faculty, and many administrators want to increase the budget amount for themselves and reduce it for instructors. “If you talk to almost any college president or chancellor…They’ll point to the Fifty Percent Law as antiquated, anachronistic and anathema to all the evidence about what’s needed for student success,” explained Larry Galizio, president and CEO of the Community College League of California.

Galizio and other non-instructional staff and administrators’ dismissal of instructional faculty result from their narrow definition of student success, which is defined as simply passing. As a result, non-instructional services are aimed to help students pass even if it comes at the expense of learning. “We recognize that students need wraparound services…there are lots of things that we do for our students now that maybe we didn’t do 20 or 30 years ago,” said Wendy Brill-Wynkoop, president of the Faculty Association of California Community Colleges (FACCC). “Success doesn’t happen just in the classroom, but it’s not going to happen without education.”

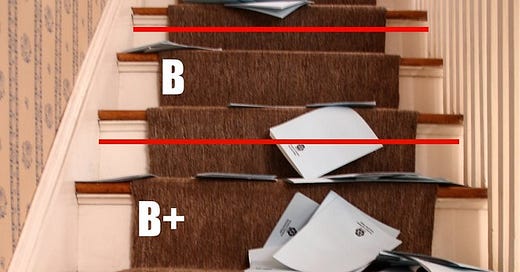

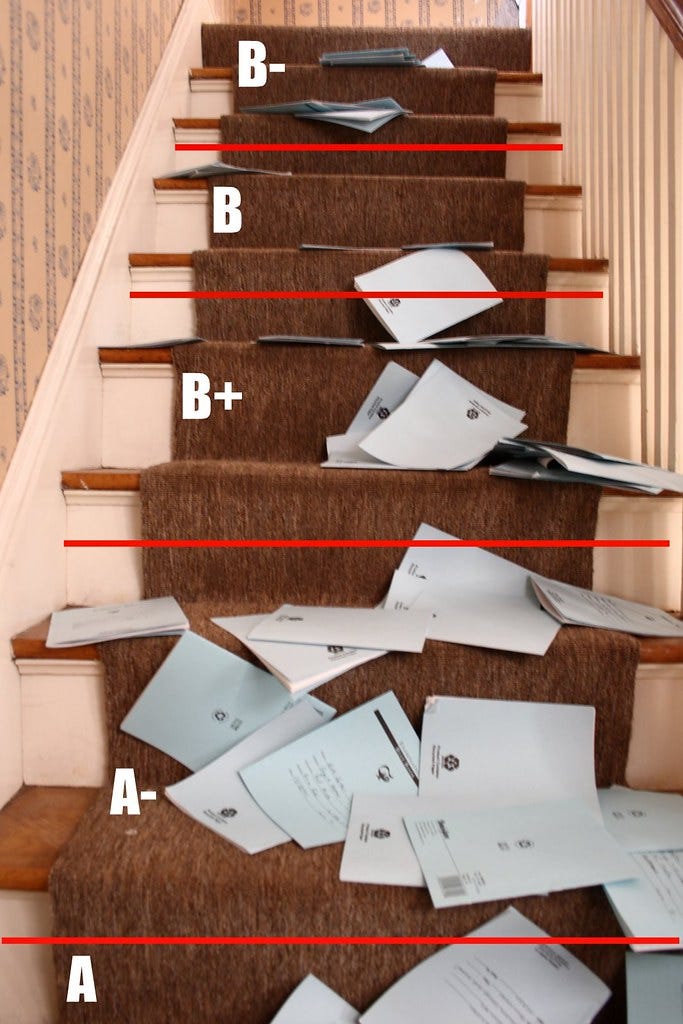

Rather than improve learning, the increasing dominance of non-instructional staff and administrators in education since the 1970s has relied on grade inflation to engender student success (also known as passing). A 2021 article in Forbes examining the rise of grade inflation and graduation rates concluded “it means that over the past 20 plus years, a significant number of college graduates would not have earned degrees if grading had stayed flat to the 1970s and 80s standards.” Indeed, although administrative bloat is justified as a necessary mechanism to improve student success, data reveal only a slight uptick in metrics such as graduation rates that are more of a result of grade inflation than actual learning. Since the 1970s, when schools began incentivizing passing over learning, grade inflation has increased, and now is normal in college and pre-college education. Since the 1960s, grades have increased on average, .15 of a point per decade, on a 4.0 scale. Grade inflation has also been a problem for so-called elite institutions such Harvard University which have witnessed a steep increase in grade inflation over the last half century.

Non-instructional staff and administrators, especially in their managerial roles, ensure that passing is privileged over learning in higher education with frivolous accommodations that conflate passing with learning; labor agreements based on enrollments which incentivize faculty to be easy graders or risk career annihilation; and faculty evaluation processes that conflate student’s passing with effective teaching.

These policies are justified as acts of social justice and equity, but mask the negative impact they are having on students. Students are generally content in the short-term to receive a passing grade because they can attain their degree and get hired for jobs that require a degree. However, if just passed along, they lack the skills and knowledge to succeed at the job and maintain employment. This threatens to produce generations of people with a worthless degree sitting under mountains of debt and unable to maintain employment, if they can even find it. Meanwhile, the school they graduated from is full of administrators and faculty who pat themselves on the back for achieving social justice and equity by passing these students along, never acknowledging that the institution took the students’ money in exchange for a degree conferred under altered metrics and inflated grades.

Beyond their economic situations, some argue that the non-instructional passing approach to education is hurting students socially by conditioning them to be narcissistic. In 2009, Jean Twenge and W. Keith Campbell warned of a “narcissism epidemic” fueled by social media which gives users an inflated sense of popularity and fame, and low interest rates on credit that give people an inflated sense of wealth. By conflating passing with learning, higher education gives students an inflated sense of intelligence. This remains true as students who perform at the average in a class think they are more intelligent than the majority of the class. One study found that two-thirds of Americans think they are above average intelligence. Worse, studies show that parents contribute to the problem as they often think their child is more knowledgeable than they actually are. The establishment news media has contributed to this since the 1980s, arguing that “Children Are Smarter Than You Think,” as one Washington Post headline proclaimed! It’s like we have become a Dunning-Kruger nation.

At the same time, campus initiatives such as low cost or free academic texts undermine the importance of faculty by conditioning students to believe that the work scholars do is trivial or worthless. Meanwhile, campus sanctioned anonymous student evaluations and calls for students to report faculty who offend them give students the sense that they have achieved a level of professionalism in education that is commensurate with their instructors. Indeed, the erosion of respect for the profession, may in-part explain, why faculty complain, when some students, high on the narcissist smoke from the non-instructional campus staff, demand (rather than request) that faculty teach the course the way the student wants it to be taught. Teachers can and should respond positively to student requests where possible, but it is worth reminding students that they are not entitled to everything they demand. The educator, as a professional, has reasons for why they teach the way they do, and if the student was conditioned to learn from the instructor instead of evaluate and judge them like a customer service review on Yelp!, perhaps they might actually learn.

There are certainly many factors shaping the power struggle between people who hold instructional and non-instructional positions on college campuses, but all stakeholders must remember that the institution is there to serve the public good and to help students learn. Short-term, feel-good rhetoric does not serve the students or the public in the long run. Instead, it sets the students up for failure and the public for economic, social, political, and cultural decay. With grade inflation, vapid appeals to equity, and empty “student-centered” rhetoric, colleges have already taken substantive steps to eradicate faculty power and reduce education to passing. Educators should remember that in the eyes of many, their education and years of service are meaningless. They think that the students who have never taught a class, and the non-instructional staff and administrators who coddle them, have all the answers for how to teach effectively. However, they will not, until the faculty are treated as the professional educators they were trained to be.

Nolan Higdon is a founding member of the Critical Media Literacy Conference of the Americas, Project Censored National Judge, author, and lecturer at Merrill College and the Education Department at University of California, Santa Cruz. Higdon’s areas of concentration include podcasting, digital culture, news media history, propaganda, and critical media literacy. All of Higdon’s work is available at Substack (https://nolanhigdon.substack.com/). He is the author of The Anatomy of Fake News: A Critical News Literacy Education (2020); Let’s Agree to Disagree: A Critical Thinking Guide to Communication, Conflict Management, and Critical Media Literacy (2022); The Media And Me: A Guide To Critical Media Literacy For Young People (2022); and the forthcoming Surveillance Education: Navigating the conspicuous absence of privacy in schools (Routledge). Higdon is a regular source of expertise for CBS, NBC, The New York Times, and The San Francisco Chronicle.